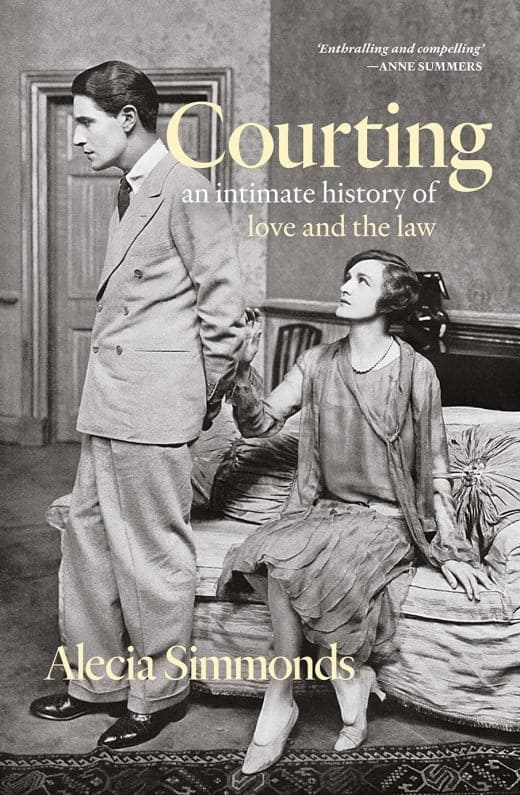

Until well into the 20th century, hundreds of jilted lovers in Australia, came before the courts to claim compensation for ‘breach of promise to marry’. In Courting, ALECIA SIMMONDS brings these stories to life, revealing the tangled histories of love and the law. Read on for an extract.

On a squally autumn day in Sydney in March 1914, Beatrice Storey, a barmaid, sued Frederick Chapman, a farmer, for abandoning her on the day of their wedding. To be precise, she claimed £1000 damages in the New South Wales Supreme Court for breach of promise of marriage, a suit that could be used to claim compensation for injuries arising from a broken engagement.

Beatrice had first glimpsed Frederick one year earlier from behind the bar at the Captain Cook Hotel. Cavalier, stocky and a ‘spinner of yarns’, he breezed into the pub ‘smelling of horses and flashing his winnings’. He told her that he had been at the Moore Park races down the road. He also said that he was 40, wealthy and a widower. After a month of giddy infatuation, he presented her with a wedding ring and vowed that he would marry her.

Almost none of what he told her was true.

Beatrice explained from the witness box that she was 30 years old when she had quit her employment on Frederick’s insistence and moved back home with her mother. Yes, she and Frederick had made wedding arrangements at St Barnabas’ church on George Street: 40 invitations were sent out, the wedding cake and carriage were ordered. She had selected furniture for their new home in Kensington, and he had gifted her £2000 to furnish the house. ‘He said he had plenty of money,’ she informed the court, ‘in fact, “money to burn.”’ The day before the wedding, Frederick kissed Beatrice goodbye on the porch of her brother’s house and told her not to be late for church.

Frederick never showed up for his wedding. He phoned Beatrice and apologised, asking her to cancel the ceremony as he had just received news that his wife was alive. The marriage would make him a bigamist. Beatrice was livid. Frederick rushed to her house and tried to console her, begging her to take the wedding ring, fumbling his way into an embrace, chaotically trying to kiss her. She pushed him away.

In the following weeks Frederick turned to ink and paper, bewailing the maddening effects of passion, confessing that the reports of his wife were ‘a yarn’ and exhorting that it was his ‘greatest wish to marry’. Beatrice converted Frederick’s love letters into legal evidence and his passion into proof, in one of the most lucrative breach of promise actions of her decade: £350 compensation for her ‘lacerated feelings’.

The next time Beatrice and Frederick appear on the historical record is 23 January 1915 at St Martin’s Anglican Church in Kensington. This time Frederick showed up for his wedding.

A little under 60 years later, in the early 1970s, a grandson of Beatrice and Frederick was also sued for breach of promise of marriage, just before the action was abolished. No newspaper bothered to report it, and we only know of the action because in 1986 a Liberal member of parliament raised it in federal parliament. The Labor MP was furious and later that day asked that the remarks be erased from the Hansard minutes. This Labor MP was the future Australian Prime Minister, Paul Keating.

Courting takes as its basis the papery remains of blighted affections found in the legal archives to tell a history of love, law and ‘lacerated feelings’ over the course of two centuries. I settle into the courtrooms of the past, lodged between the scribbling men of the press and the tittering, jeering crowd, and report on a series of women and men who appeared before judges and juries offering proof of their endearment: love letters, gifts, jewellery, gossiping neighbours, expert witnesses, trousseaux and tales of misplaced trust.

Frederick never showed up for his wedding. He phoned Beatrice and apologised, asking her to cancel the ceremony as he had just received news that his wife was alive.

Some went to court seeking compensation for lost wages or diminished social status, others for wounded affections, and many more, like Beatrice, were using the action to pressure their partners to marry them. I use these litigants’ life stories to unpick the entangled histories of love and law, and to explore what breach of promise actions tell us about the history of love.

A hidden museum of love can be found in the legal records, which lie bundled in dust-choked boxes across the country. Often the files appear corpulent, the ribbon straining like a belt. They’re filled with all the documents you’d expect to see in a legal case but sometimes unusual things fall out: love letters, train tickets, photographs, receipts for negligees or engagement rings. In Syrian hawker Cissie Zathar’s file from 1907, I found a yellowing strip of antique-white lace affixed with a pin to one of her letters to Moses Hanna, her lover in Redfern.

The viscerality of these documents still cuts through me. How could these most intimate, secretive, howling letters end up bundled inside a writ? For the most part, the inner lives of working-class people do not make their way into archives. Breach of promise cases, I discovered, were an exception. The court transcripts give us the life stories of people who would never have thought to write an autobiography.

Breach of promise is now abolished, seen as a quirky relic of the Victorian era. Women are not dependent on marriage as they once were, and a failed relationship does not relegate women to the status of damaged goods. If Beatrice Storey had been left at the altar today, Frederick Chapman would not have been forced by the state to compensate her for her hurt feelings or for any economic losses she sustained.

Today’s Beatrice would likely try to overcome her pain by reading a self-help book or talking to friends, family and psychologists. The advice she would receive would revolve around the virtues of resilience, the balm of commodity culture (go out and buy yourself a new dress!) and interrogation of her own psyche (why had she been attracted to such a cad in the first place?).

The stories in Courting, track why this change occurred and asks how we might imagine an ethics of intimacy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR