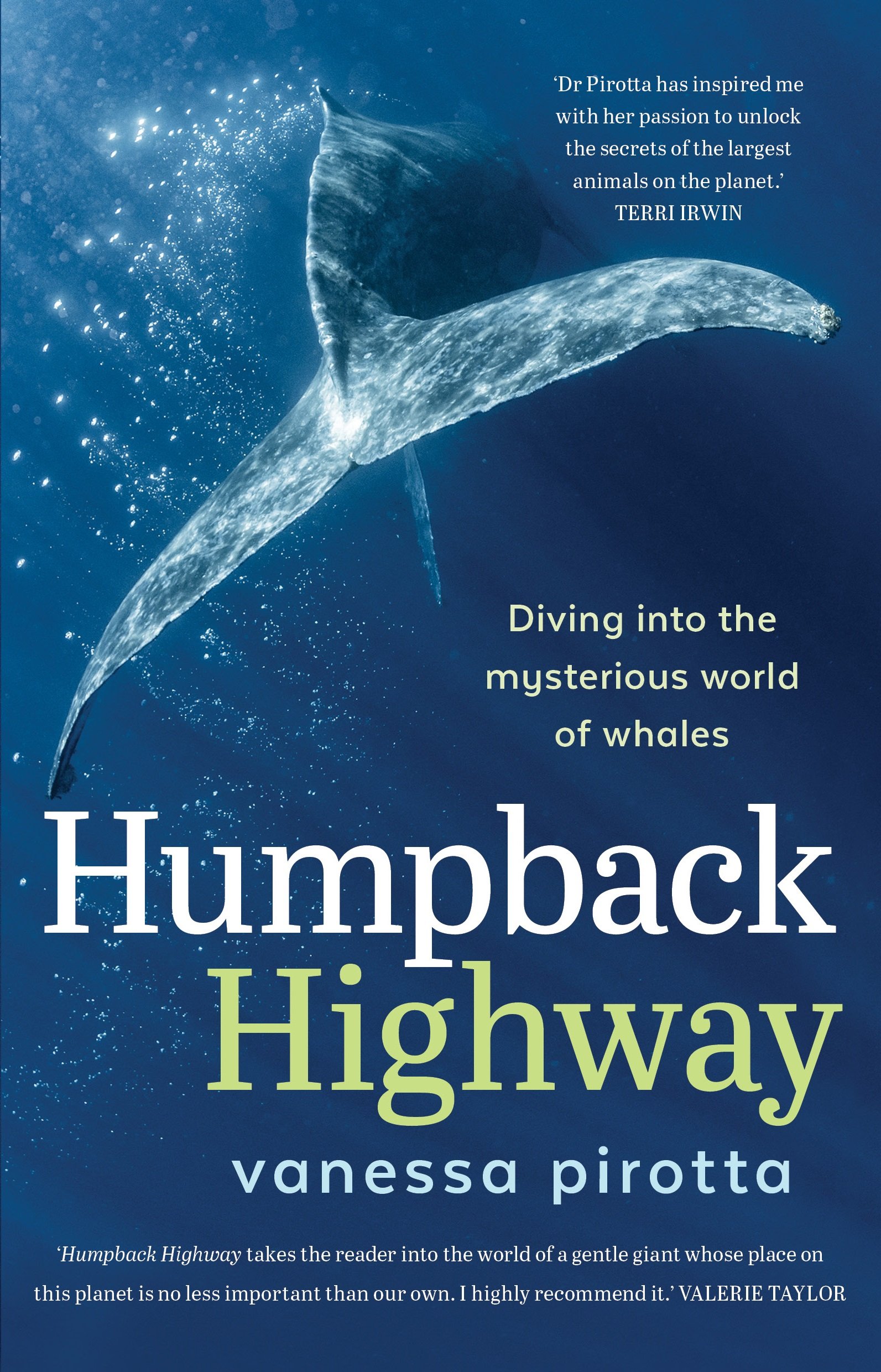

Acclaimed wildlife scientist Vanessa Pirotta has been mugged by whales, touched by a baby whale and covered in whale snot. In Humpback Highway, Pirotta dives beneath the surface to reveal the mysterious world of humpback whales.

Listen to a podcast and read the first chapter.

CHAPTER 1

Migaloo

I’m dedicating my opening chapter to a whale I’ve seen only once in my life, briefly and from a distance. It was memorable though.

On a sunny winter’s afternoon in 2014, I was at my desk at Macquarie University, going through data I had collected from the field. I’d spent days on end from dawn to dusk at the whale deck at Cape Solander, in the Kamay Botany Bay National Park near Kurnell – a beautiful cliff-based location in Sydney’s south. I was researching an idea to prevent whale entanglement in fishing gear. My good mate Wayne Reynolds called. A dedicated citizen scientist who has 30 years of whale-watching experience, he was down at the whale deck. Excitedly, he told me that he had just spotted Migaloo.

I dropped everything. I knew I had to head to the closest headland for a chance to see him. Wayne was an hour’s drive south. Migaloo would have travelled too far north by the time I made it there. So I headed towards the coast, using every toll road possible. Around 30 minutes later I arrived at Maroubra Beach. There was a risk Migaloo might have swum out to sea, away from land. Fortunately, he hadn’t. I chose absolutely the right place to be.

Migaloo is part of the Australian east coast population and was first sighted off Byron Bay, Australiain 1991. He is known to migrate in both Australian and New Zealand waters.

There he was. I was staring at the world’s most famous humpback whale. He looked like a moving iceberg. Because he is so brilliantly coloured, he glowed. This made him extremely visible from 2 or 3 kilometres away offshore, even when he was underwater.

At first, I was alone, as Migaloo and another whale were travelling north, making their annual migration: Pfffffffffft, pfffffffffft, went the sound of two whales blowing in the distance. They both surfaced. One dark whale and one illuminated white whale. It was incredible.

Soon the word got out. Sydney whale-watching boats started making their way to the two whales. When I worked as a naturalist on these boats there were always first-time whale watchers on board. Can you imagine if you got to see Migaloo on your first whale-watching trip? How incredibly lucky would that be?! To see Migaloo is a bucket list item for many people around the world. So, why is Migaloo so special? What’s the deal? Let’s explore what we know about him.

Paul Hodda of the Australian Whale Conservation Society first spotted Migaloo off Byron Bay in 1991. Hodda was at the Cape Byron Lighthouse, the most easterly point on the Australian coast and a great place to spot wildlife. At the time, Migaloo was estimated to be between three and five years old.

In 2022, a white humpback whale calf was spotted off the coast of Costa Rica (resighted in 2023 in Peru waters and named Spirit Whale), and in July 2023 another all-white calf was observed at Western Australia’s Ningaloo Reef.

Images of the latter did the rounds on social media showing a calf who looks like a mini-Migaloo making its southward journey to Antarctica. We will watch out for it in the next few years and, as this animal grows, I’m sure scientists will be keen to determine if it’s a true albino.

Some speculate that Migaloo has offspring, but this has not been confirmed. Given that Migaloo is one of 40 000 plus humpback whales that travel up and down the Australian east coast, finding his offspring, for genetic confirmation, would be like finding a needle in a haystack.

Genetic analysis has helped us identify other things though. Sloughed skin samples (fallen off skin left over on the sea surface) collected by scientist Dan Burns’s team from Southern Cross University in 2004 confirmed Migaloo is male, as was his travelling companion at the time.

Scientific analysis documented by scientist Andrea Polanowski and others in 2012 confirmed Migaloo’s albinism was caused by ‘a frameshift in the tyrosinase gene’.

Put simply, Migaloo looks the way he does because he is lacking the pigmentation which gives skin its colour. So, through genetics, we can confirm Migaloo is male and albino, unlike other whitish whales.

Being white makes Migaloo easy for non-scientists to recognise. He stands out. That’s why so many people know about him. His conspicuous appearance has led to regular sightings over years that enable us to learn details about him, such as his migration patterns and the company he keeps. Up close, or through photos, you can distinguish individual humpback whales from each other. So we know that Migaloo has been sighted swimming with a whale named Milo multiple times. Milo has a darker colour on his/her backand a whitish lower body. (Milo was named by a citizen scientist because of a resemblance to a well-known chocolate milk drink here in Australia.)

Over the last few years, I’ve been working closely with scientists and citizen scientists to document Migaloo’s movements. A citizen scientist is not a scientist, but someone whose activities can help scientists.For example, people flying drones just for fun might capture rare whale behaviour; others might dedicate part of their weekend to keeping an eye out for eagles using an eagle camera (like my whale-watching friend Cathy Cook). People are fascinated by Migaloo and efforts to try and spot him generate excitement on social media, as well as in the mainstream media. I’m often asked about Migaloo by both the media and my international friends in the marine community. He’s a celebrity for many whale watchers.

It’s always fun and exciting to work with people across Australia trying to spot a single whale. I have worked with some passionate and dedicated citizen scientists including those who run the White Whale Research Centre (especially Oskar Peterson and his daughter Samara) and others who have seen Migaloo several times like Leigh Mansfield and Jodie Lowe. Migaloo even has his own website (migaloo. com.au) and X (formerly Twitter) handle (@Migaloo1), both of which are useful places for sharing information.

In 2022, I pulled together the first official sighting record for Migaloo, prompted by claims that Migaloo was dead after a two-year absence. On a Friday morning in June that year, smack bang in the middle of the northward migration, I did a live cross interview with breakfast TV show Sunrise. They had organised a vessel for me to venture out to the humpback highway. The swell was not kind that day so we stayed between the heads on Sydney Harbour (this suited me as I was pregnant at the time).

The Sydney heads mark the intersection of the harbour and the ocean, where you turn onto the humpback highway – the water corridor for migrating humpback whales travelling up and down the Australian east coast – either left/north to Queensland or right/south to Antarctica. I had my big lens and camera ready to spot wildlife but there was nothing. Always the way for television. During the cross, I spoke about the search for Migaloo who hadn’t been seen since 2020.

The next day, I was invited into the studio to discuss whale migration on ABC’s News Breakfast. I reminded listeners about whale safety and to give whales plenty of space when whale watching on the water or using drones, and not to harass them. Of course, I also talked about Migaloo.

A few hours later, Lorna from the White Whale Research Centre contacted me. The unthinkable had happened – a white whale had washed up dead on a beach near Mallacoota in Victoria. The spotter, who had contacted the Migaloo sighting network, had photos to prove it. You can imagine how I felt when I heard this, especially after telling Australia that Migaloo was only in his early 30s (relatively young for a humpback whale) and that his absence didn’t necessarily equal his death. What timing!

I didn’t know it at the time, but this was the start of a four-day Migaloo frenzy.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Vanessa Pirotta is a wildlife scientist, woman in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths), science communicator and vessel operator. Vanessa has been studying whales in Australian waters and around the world for the last 14 years. Her work uses clever new technologies to help conserve wildlife in both marine and terrestrial environments. Vanessa has become a powerful role model for younger generations, connecting young minds with science around the world.